I arrived in Paris on a cold, winter’s morning in 2006. It was just after 8am by the time I had made it to the nearest train station to the Cité and the sun would not come up for another half hour. I bundled myself and my bags into the first open café I could find to have some breakfast, keep warm and pass some time until the Cité would be open. On arrival at the Cité I was shown to the lovely warm studio. I quickly settled myself in and headed out to buy some food supplies. Over the next couple of weeks I started reading, thinking, making notes and sketches. I braved the cold of Paris in winter, walking a lot, visiting galleries and museums and generally orienting myself and trying to get a feel for the place.

High on my ‘to do’ list was to view a series of comparative physiognomic studies between human and animal faces by 17th century French painter, Charles Le Brun. I was fortunate enough to be able to secure an appointment at the Department of Graphic Arts at the Louvre in order the view two large volumes held there which comprise the bulk of this extensive body of work. This was an extraordinary experience. I was taken into a large, ornate, high ceilinged study room in the Louvre, where I joined another three scholars, all of us seated at one of a number of reading tables. Here I was delivered two enormous volumes, bound in 1803 for Napoleon, which contained virtually the entire series of these works. The volumes contained engravings taken from Le Brun’s final pen and ink drawings, as well as the original pen and ink drawings and numerous studies by Le Brun in ink, in pencil and in black chalk, from raw initial sketches to the finished drawing in ink and wash. These drawings were clearly pages taken from sketchbooks, and it was an extraordinary experience to be able to turn the sketchbook pages, which were glued down one side only, to see other sketches on the backs of the pages. I was there four hours, carefully turning the old pages to reveal more and more of this amazing body of work.

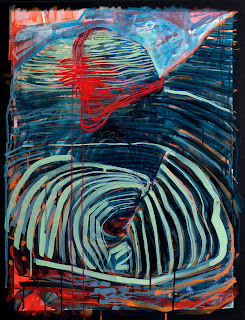

While better known as a painter of substantial stature in the French Academy, Le Brun produced numerous drawings exploring the physical congruities between human and animal faces, and suggesting consequential emotional and/or behavioural human ‘types’ based on an individual’s physical similarities to certain animals. It was with these works of Le Brun’s in mind, with their morphing of human and animal, that I began working through ideas that resulted in two series of self-portraits in gouache, watercolour and ink on paper. In four of these works, the heads of ‘farm’ animals replaced my eyes, while in the second set of four paintings my eyes were replaced by the eyes of ‘farm’ animals.

I was not particularly satisfied with the first four self-portraits (those with animal heads replacing my eyes), as I felt found the incorporation of the entire animal head into my face was not particularly successful in engaging the viewer with the animal’s gaze, as was my intention for these works. Fortunately, however, at the time I was working on these images, I became aware of the annual agricultural expo that was being held in one of the outer suburbs of Paris. This provided me with a perfectly timed and highly fortuitous opportunity to photograph ‘farm’ animals at close quarters, and in particular, to be able to photograph their eyes, which I was then able to incorporate into the second series of four self-portraits where my eyes were replaced by those of a pig, a chicken, a cow and a sheep. These images were much more successful as the use of animals’ eyes to replace my own meant that the viewer was simultaneously met by the gaze of a human and an animal they might normally eat.

On my return to Hobart I made a decision to produce larger scale, more resolved versions of the Alternative Points of View series of self-portraits with animal eyes and to compliment these with a companion series of works depicting ‘farm’ animals with their mouths replaced by my mouth.

In those images where my eyes are replaced by those of an animal there is the implied notion of seeing the world through the eyes of another, that ‘other’ being a ‘farm’ animal, and thus giving consideration to the animal’s perception and hence experience of the world. In the other images, where the animal’s mouth is replaced by my mouth the viewer is prompted to consider what the animal’s point of view would be in a verbal rather than a visual sense of the phrase. The mouth in each of these four images is shown open, as if at the point of enunciating a word. Through the depiction of a talking animal the issue of animals being ‘dumb’ or mute is raised and the idea of animal advocates/activists describing themselves as a ‘voice for the animals’# is addressed.

The front-on format of these portraits intentionally subverts the idea of the animal as a passive receiver of actions by humans. In all cases, the viewer’s gaze is met by that of the animal/human who looks directly back at them. This recognition of the animal looking back – having its point of view – profoundly affected Derrida, who writes about how ‘… it [the animal] can look at me. It has its point of view regarding me.’# This is a key concern of the Alternative Points of View series, as the viewer is prompted to put themselves in the animals’ place – to consider an alternative point of view from that which places humans as dominant and superior and the animals as commodified, oppressed, objects of that domination.

While digitally altering the image to crop and reverse the animal eyes for the images in Alternative Points of View I noticed something strange: When the two animal eyes were pushed together after one had been flipped, the resulting image was uncannily primate (and thus human) like. What’s more, when the resulting pairs of animals’ eyes were scaled correctly and placed over my eyes on a photograph of my face, there was a surprising and unanticipated congruity – a lining up of features – between the brow-line and nose, without any need for adjustment other than scale. This prompted the construction of the Second Sight series, which exploited this uncanny anatomical conformity.

It was never my intention that there would be a seamless morphing of the eyes into my face, in fact quite the contrary. I specifically wanted there to be a shift between the anatomical congruity and hence believability of the image against the somewhat crude mask-like quality of the animal eyes on my face. This visual shift reflects a metaphorical shift between human and non-human animals – a recognition of both similarity and difference that is behind the numerous tensions and incongruities in our attitudes and actions in dealing with various non-human animals, and which is particularly evident in the way we think about and exploit ‘farm’ animals.

Without any doubt, the time I spent in Paris was of great influence on my work and was instrumental in the successful completion of my PhD (I was part way into my PhD at the timer of the Residency). The timing of this trip couldn’t have been better, and returned reinvigorated and with a renewed sense of clarity about the direction of my research project. The opportunity to focus exclusively on one’s work in such a stimulating environment and without many of the prosaic distractions of day-to-day life cannot be underestimated in its importance.

.jpg)